|

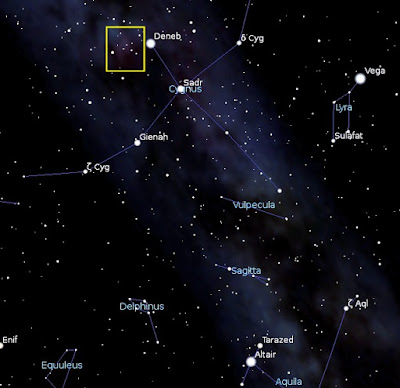

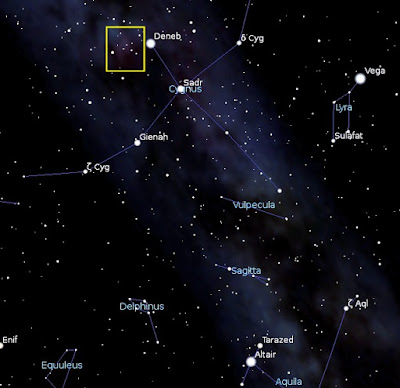

Stellarium map showing field of view

|

On October 24, 1786, William

Herschel, observing the area of sky around Deneb (the alpha star of the

constellation Cygnus) from Slough,

England, noted

a “faint milky nebulosity scattered over this space, in some places pretty

bright.” The most prominent region was catalogued by his son John

Herschel on August 21, 1829. It was listed in the New General Catalogue as NGC 7000, where it

is described as a "faint, most extremely large, diffuse nebulosity.”

On December 12, 1890, the German astrophotographer Max Wolf noticed

the characteristic shape of the eastern part of the nebula on a long-exposure

photograph, and dubbed it the North America Nebula. In addition, in a paper of

June 10, 1891 he described the region near that nebula as photographed on a 3

hour plate taken on June 1 of that year. However, an accurate position of the Pelican

Nebula had to wait until Sep 7, 1899, where the object was described by

British astronomer Thomas Espin.

In his study of nebulae on the Palomar Sky Survey plates in 1959, American

astronomer Stewart Sharpless realised that the North America

Nebula is part of the same interstellar cloud of ionised hydrogen as the Pelican

Nebula, separated by a dark band of dust, and listed the two nebulae together

in his second list of 313 bright nebulae as Sh2-117. American astronomer Beverly T. Lynds

catalogued the obscuring dust cloud as L935 in her 1962 compilation of dark

nebulae. Dutch radio astronomer Gart

Westerhout also detected the HII region Sh2-117 as a strong radio emitter,

3° across, and it appears as W80 in his 1958 catalogue of radio sources in the

band of the Milky Way.

One of the most famous bright nebulae in the heavens, the

North America Nebula is shaped very much like its namesake. Despite its

relative brightness, its large size and low surface brightness make it

undetectable with the unaided eye except in very dark skies, and even then only

by using special filters to increase the contrast of its line radiation. The North America and Pelican nebulae (IC 5070) are part

of an approximately 100 light year-wide ionised hydrogen region. Their shapes

and apparent separation are due to clouds of obscuring dust lying between us

and them.

What star or stars are responsible for heating the gas has

long been unknown, but recently the 2MASS

infrared telescope, concentrating on the area obscured by dust, has shown that

there is a massive O-type star in the general area of the nebulae, which is the

most likely source of their radiation. Estimates of the distance of the North America and Pelican nebulae vary considerably,

ranging from as little as 1500 light years to as much as 2200 light years.

The image above maps the hydrogen alpha emissions of the

region. This represents “first light” of

my new wide-field imaging system, comprising of a Samyang F2 135mm focal length

lens coupled to a Starlight Xpress SX PRO-694 camera. This gives a 5 x 4 degree field of view.

To carry the lens and camera, I refurbished my old Vixen

GPDX mount, re-greasing it and carefully adjusting the RA and declination worm

drives to try and eliminate the horrendous backlash that had always plagued it.

I also (reluctantly) retired its old and increasingly unreliable Skysensor

control unit, replacing it with a Skysensor EQ5 upgrade kit which allows me to

control the mount via EQASCOM.

Although such a short focal length system probably doesn’t

need auto-guiding, I had a spare guide camera and a Vixen 450mm focal length

guide scope, so I thought I may as well use them.

The set-up is intended to be a portable one, although I will

be setting it up in the same position in my garden. I Araldited three steel washers to the

hard-standing where I would be setting up the tripod, and used the GPDX’s

excellent polar-scope to polar align.

It all seemed to work pretty well first time. PHD reckoned

the polar alignment error was only around 1.5 arc-minutes, with an RMS guiding

accuracy of around 0.6”, way better than needed (and better than my observatory

Avalon mount!), so I think the mount

refurb went pretty well.

At the moment I am manually focussing the lens but at F2, it

is extremely sensitive and I may need some engineered assistance. Spacing between the lens and the CCD camera

is also critical. Fortunately I managed

to find an assembly of various adaptors that connected the lens to the camera

via my old ATIK manual filter wheel that manage to land the Ha focus point

exactly on the “infinity” point of the lens.

Manual focussing required a deft touch but was relatively

easy using the focus indicator on the Astroart camera control module. For

starters, I shot 6 x 300 second exposures in Ha at F2 (via an old 12nm Ha

Astronomik filter) and was very pleased with the sharpness and detail in the

single subs. There was a small amount of flaring around the brighter stars that

I attributed to the filter and some small distortion of the stars in one corner

of the image field, but nothing disastrous.

|

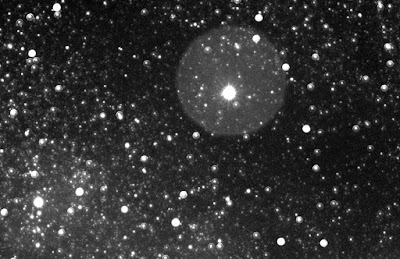

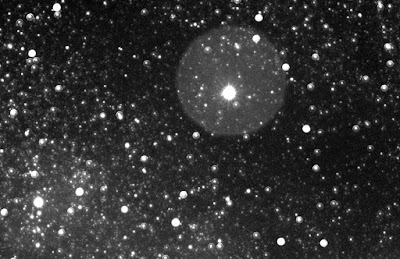

OIII flares around stars

|

Attempting to use an old Baader filter for OIII imaging was

a complete washout however, as the flaring around all stars made the sub-frames

unusable. That filter will have to be replaced, hence the mono image above.

I used Starnet to remove the stars from the stacked Ha data

as I found the snowstorm of the Milky Way to be distracting. This allowed some

minor selective sharpening and stretching of the nebulosity, although the data

was pretty good even though I only had 30 minutes-worth of subs. I restored the stars by layering a

“de-stretched” and slightly Gaussian-blurred version of the original stack over

the Starnet version in “blend” lighten mode.

References:

https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap171201.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_America_Nebula

https://cseligman.com/text/atlas/ngc70.htm

https://cseligman.com/text/atlas/ic50a.htm#ic5070